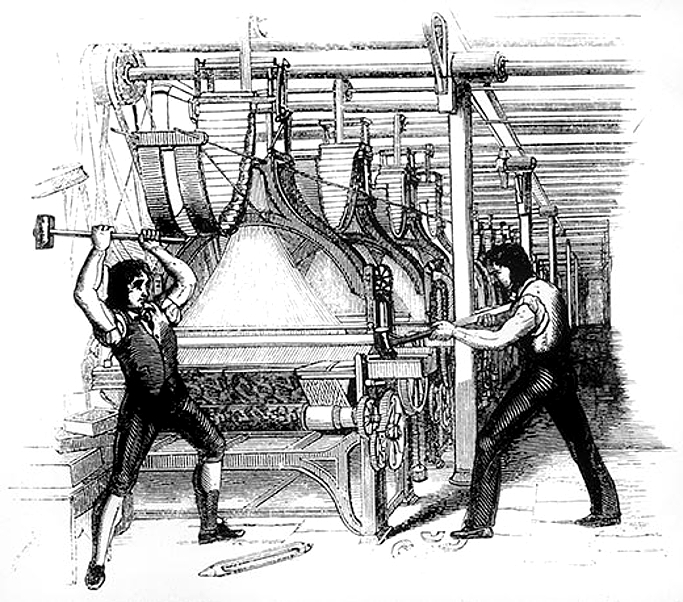

Many captains of technology are openly predicting the demise of humankind from advancements in automation and artificial intelligence (AI). Luddites – 19th century workers who believed machinery was threatening their jobs – said much the same thing, sans AI.

We must recall that mankind has created, endured, and grown from nearly every technological advancement. Luddites did not get their mill jobs back, but their descendants are doing quite well and wearing much less expensive clothing made from machines. My semiconductor industry all but did away with vacuum tubes, which would not be suitable for the smartphone in your jacket pocket. Milking machines did replace milkmaids, but I am hard pressed to find a modern woman who wants that job.

Why then are tech titans loathing automation and AI? For the same reasons Luddites feared the weaving machinery – they discounted human flexibility and overestimated the displacement power of technology.

Automation and scribes

I suspect the Vatican is quite happy with Microsoft Word as compared to hiring warehouses full of scribes when it comes to mass production of Bibles.

Automation exists to save manual labor. In my lifetime, banks employed rooms full of people who manually reconciled accounts on the original spreadsheet – large pieces of paper with pre-printed grids of columns and rows. When IBM brought computation machines into banks, there was a transient (and isolated) spate of unemployment among the accounting class, who were quickly absorbed into other lines of work.

Why then are we fearful of new machines designed to reduce human toil further? Some fret that lower income wage earners will be forever displaced, which was the Luddites’ claim. Others sense a need to increase job opportunities to meet the needs of the population, but fail to incorporate the slumping birth rates (as side effects of general prosperity) or baby boomer old age attrition. Indeed, if, as one analyst group maintains, there is a $2T economic drag from needless regulations, our tech industry leaders would do better to focus on the debilitating effects of Washington rather than robotics.

The fact is that automation temporarily displaces workers, and tends to do so in singular industries. Currently, the fast food industry is a prime target, especially once $15 per hour wages brings annual price parity in line with automated burger flippers. But that is one industry, and the change will neither be instantaneous or ubiquitous. Displaced employees will adapt.

We then have to ponder the economic benefit of automation and how that affects the general populace. We lost a thousand Luddite weavers, but the cost of fabric and clothing fell for everyone (net public benefit). When tractors automated much of agriculture, it contributed to ever rising crop yields, and lowered the price of food (net public benefit) from 41 percent of a household budget to 19 percent over the last century. However, automation may well replace migrant farm workers.

What is clear, then, is that economics, like life, finds a way. A few jobs may be eliminated, but the displaced workers either find alternative employment or the next generation will simply avoid the automated industries. Since some industries cannot (yet) be automated, job migration between fields remains possible.

Authentic Intelligence

Aside from reducing human toil, technology can augment or amplify general prosperity. AI will contribute, yet will not replace jobs at a rate anywhere near mechanical automations. Artificial intelligence still requires authentic intelligence, because the first order of business is always to ask the question, something AI presently cannot do well. We humans are still pretty good at inquiry.

AI shines at repetitive learning and numerical discovery. In medicine, AI will radically refine patient diagnostics and reduce human suffering (as well as malpractice litigation). It will maximize crop yields, reduce water usage, optimize energy consumption, and much more. These make for a much more economically efficient society, which benefits everyone. In the end AI will create jobs, not eliminate them. These technical applications require a range of workers, from field techs who repair sensors to data scientists who model from massive data sets. It takes people in IT to run the servers and configure the routers. It needs people assembling components to read and control devices. And the flood of serviceable data opens vistas for new entrepreneurs and opportunities for even more jobs.

It might even create jobs for service techs to set up or repair your dairy cow artificial insemination machinery. Sadly, the bull is out of a job.

What does not change

Jobs will change. The economy will expand, and our need to toil will be reduced. This will not decimate mankind – it will elevate it.

Society still needs good mothers and fathers to raise great children. Automated homes, greater general prosperity, and shorter work weeks will grant parents more time to nurture their children; and given the trends in home schooling paired with online education, the only endangered job might be that of a public school teacher. Automated automobiles will give commuters back wasted hours. We will have more leisure, and more time for public service.

That is the promise of all technology. We are, after all, humans. And as humans, our societal institutions – religion, politics, policing, school – still require direct contact, and benefit from more of it. Fear not, then, AI and automation – for in the long run it improves mankind by liberating us to be more human.