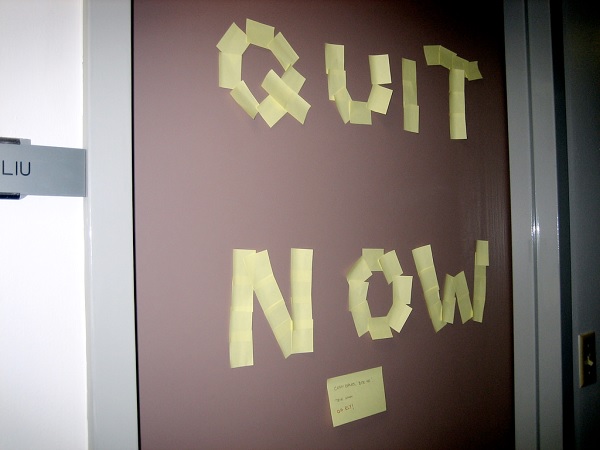

Sometimes you have to quit to get ahead. This happens when other things are holding you back.

Ray Zinn, the longest serving CEO in Silicon Valley, quit his job to found Micrel, the most consistently profitable semiconductor company in Silicon Valley. Hear his story about when to know when to drop the dead weight of a job.

Guy Smith: Hello everybody and welcome to another episode of the Tough Things First podcast. I am your guest host today, Guy Smith, and as always, we’re here with Ray Zinn, the founder and CEO of Micrel Corporation and the longest serving CEO in Silicon Valley. Hello, Ray.

Ray Zinn: Hello, Guy. Thank you for being with me again today.

Guy Smith: Thank you for being with me. I pick up more wisdom per unit of time sitting with you, than anything else I do during my day, that’s for sure. I want to go back in history. You had an interesting event, which led to you becoming an entrepreneur. You quite famously got fired for being aggressive and selling a product that basically didn’t exist. As a side note to all the listeners, I’ll mention is a product, which is now a standard piece of equipment in every semiconductor manufacturing facility that there is. For the audience, give us a short version of that origin story. What happened that caused you to suddenly say, “I’m going to go start a business?”

Ray Zinn: That’s a good one, Guy. I love telling this story, because it really rings true. I never thought of myself as starting my own company. I was perfectly happy working where I was. I was working for a company called Electromask. They made photo mask equipment for the semiconductor industry. Those were pieces of equipment used to image the circuitry onto the wafer, silicon wafer. For those that don’t know what that is, that’s a piece of almost like glass, but it’s gray colored, and it’s very thin, and it’s round, and they call it a wafer because of its physical size and looks. They made equipment that allowed the semiconductor manufacturers to create the image on the wafer. I was told by my boss, this was back in the early seventies, to go and visit a company called Texas Instrument down in Dallas Texas. When I went down there, we were a very small company and TI’s a very large company, and they didn’t want to see me.

In fact, they rudely told me to leave. Here I’ve flown all the way from, as you would, San Francisco to Dallas and I wasn’t very happy about being asked to leave and just get back on the airplane and fly home. I told my boss that I was rudely told to leave and he said, “Well, any good sale’s guy doesn’t give up. He goes back again.” I said, “Ah, okay.” I was a young kid, I was just really young, I was in my early thirties. I jumped back on the airplane, went back up there again, and this time they escorted me out with two security guards and actually threw me down some steps and I tore my pants, my suit pants. I was very unhappy and told my boss, “That’s it. I’m not going to go back there again.” He said, “Ah well, you’ve got to get into TI, you absolutely must get in there.” I said, “They don’t have the southern hospitality I was expecting and so I don’t really think, I don’t want to go back.”

Anyway, he implored me to go and visit them again. This time when I went down I had to come up with some reason to get in the door so that I wasn’t going to be thrown out again. I didn’t wear one of my new suits again, because I was afraid it was going to get torn, so I wore one of my older suits expecting to get thrown out. When I went in there, I dreamed up this idea of when the receptionist asked me who … When I asked to speak to this particular individual, the receptionist asked me, “Well, who may I say is calling?” I didn’t want to give my name again, so I just said, “Tell him his brother’s here.” I then … She called up to speak to the TI employee and told him that his brother was down in the lobby to see him. Down came this individual waltzing down the stairs and he looked around, he didn’t see his brother, obviously, and so we went to the receptionist, receptionist pointed toward me.

I was sitting on a couch and I had this Cheshire grin on my face and he came over. He said, “Well, how dare you?” He was so mad, he was just red in the face and angry. I said, “Well, aren’t we all brothers and sisters anyway?” He laughed. He thought that was a fun way of getting him to come and acknowledge me. He took my hand, lifted me up off the couch, and he said, “Come up to my office.” We went up there and so I began talking to him about what they needed, what kind of the direction the industry was going to head, and what they would like to see. On the way back to the Bay area, I thought of an idea of how we might create a new piece of equipment, a new concept, called the wafer stepper. I was working for a small company, and didn’t have a lot of resources, and so I didn’t want to break it to him because they were already strapped doing what they were doing anyway.

I kept it to myself and just tried to get TI to buy other equipment that we had and kept using this new piece of equipment, this wafer stepper as kind of like a carrot. I tried to get them to buy the stuff and they just kept bugging me about this wafer stepper. Finally, I created this idea of how we might develop it and design it, but my company never knew about it. I thought I could just keep putting TI off and still get in the door with some of our current equipment. That didn’t work. They absolutely were emphatic, they wanted to buy this equipment, and since I made it sound so inviting and so real, because I wanted to, given the fact that I wanted to get in the door, I made it sound very … Like it was imminent, like we were ready to start producing it any day, that they finally just said, “We’re going to give you an order.”

They gave me an order for three of these systems, but they wanted a price, and so I had to think about what kind of price to charge them. I came up with this idea, this price of this system. The current system that they were purchasing to do a similar job was about $50,000. I thought, “Well, if I had the price high enough, they wouldn’t give me an order.” When I told them that the price was $800,000, which is 10 times, more than 10 times the price of their current solution, they didn’t blink an eye, they gave me a PO for three of those. Here I am, here I got this order for $2.4 million. Anyway, so I told my boss about it, because TI kept bugging about the delivery on it. He was very upset and he was infuriated with me, because they were already strapped and didn’t really have an opportunity to work on it.

I became kind of persona non grata at the company and ultimately, they invited me to leave, saying that I really shouldn’t work for anybody else, because I didn’t seem to fit in, that I really should go off on my own. I went home that evening after being down in the LA area visiting my company and told my wife as I walked up the stairs, “I was never going to work for anybody ever again.” She said, “What are you going to do?” I said, “I don’t know, I’ll think about it. I’ll have to come up with something, because I’m not going to work for anybody ever again.” That was mid-1976 that that happened. Since July of 1976, I’ve only worked for myself.

Guy Smith: The short story there and I’m so amused by this, is that you conceptualized the wafer stepper and despite your best efforts to not do it, managed to sell it to TI anyway, and then had to hand a purchase order for this nonexistent equipment to your boss. That’s when they said, “You really probably should go work for yourself.” That led to 37 years of almost continuous profitability, only missed one year, and that was due to a massive write off of a redundant facility that you had, so that’s … I think getting fired was actually a great thing for you. Do you think you would’ve ever started a business had you not been fired?

Ray Zinn: Probably not. I mean, I can’t say for sure. Years later, I think it was in the eighties, Tom Peters wrote a book called In Pursuit of Excellence, and he wrote in his book that, “If you’re not getting fired, you’re just not trying hard enough.” That rang true with me, because I was trying pretty hard and I got fired. For all of you out there, hey, it’s okay to get fired, because that means you’re trying harder and if you’re not trying harder, maybe you should try harder, because you really are not putting forth your best effort unless you’re pushing the limits. That’s what I did. The reason I started Micrel was I just said, “I’m going to come up with a company that I can really have control over and be able to run it my way and not be saddled with all these other corporate rules and regulations that these other folks had to suffer with.”

Guy Smith: Well, short of being fired, what should somebody look out for in themselves that tells them that they really should work for themselves? I mean, there are a lot of geniuses here in Silicon Valley, a lot of people who have an idea or a momentary spark of inspiration, but what is the signal that they should see in themselves that say, “No, I’m really going to do better if I go strike out on my own.”

Ray Zinn: Well, short of getting fired, and I still think that’s the way to do it, is you get yourself fired and then you have to go do something else. Short of that, is if you have a knack or a feeling that you’d like to start your own company, you think you have the energy, you have the wherewithal to do it, hey, give it a shot. I mean, as long as your family’s willing to support it and you’ve got the resources to go and do it, do it.

Guy Smith: Well, and that’s probably the signal, which is going to go out to Silicon Valley, because there are a lot of people here who want to follow that dream. There’s a lot of examples here in Silicon Valley of people who just had a good idea and had enough guts to go do it and they made marvelous things happen like Ray did for 37 years at Micrel. If you want, and you should do this, go by the Tough Things First website, ToughThingsFirst.com, there’s a series of social links up at the top. You can connect directly with Ray Zinn through that path and if you haven’t already, and I will drive this point home, do get a copy of his book, Tough Things First, because it is going to be a tour de force education on what it takes to be a leader, to be a manager, to be an executive, to be humanistic in your approach to life, and it is arguably one of the best business and perhaps life books that you’re going to read this year and maybe ever. Thanks again and tune in for another episode next week.